ROTHKO, AGAIN, SORT OF, ALONG WITH A BAD PUN

The man that taught the online photography classes I took during COVID was a lifesaver. Through him, I found a new community of people, interested in a different kind of language than the words I was drowning in teaching online. But our teaching styles differed in one way: when the photo went up on the screen for review, he always asked the artist to comment first, to explain their vision and intention. In my writing workshops, I ask the writer to refrain from comments until others have shared their impressions.

In response to last month’s post on Rothko, one of the photo critique group members commented that one needed to consider what the viewer brought to the artwork. The viewer’s perceptions can be valid all on their own, even if they don’t match artistic intent, she wrote. So I’ve been thinking about that and what we mean by valid.

First, I agree—to an extent. It reminds me a little of therapy, where a feeling is always valid. If you have it, you have it. To some extent, a person’s first reaction to an artwork is like that: how you feel is how you feel. What it means to you could certainly be different from what it means to those around you, and that feeling is neither right nor wrong; it just is.

But.

I like to tell my students that a poem can’t mean just anything, in the same way a painting doesn’t mean just anything. There are cultural and artistic parameters. Romeo and Juliet is about love, it’s not about a chicken crossing the road. But it’s also about fantasy and family and deception. Thus, it offers a range of interpretations and, depending on where a person is in their lives, they might hook into one meaning over another.

Rothko’s a harder case because he doesn’t give us a lot to go on. And it depends on how much knowledge of him, his forms, his thinking, we bring with us to our viewing. That’s true of any medium. What does a giant blue, yellow, and white rectangle mean? Is what it means different from how I feel about it? At least in representational painting, there are objects to help guide me, but in abstract art (especially Rothko’s claim that he was abstracting emotion), how do I approach what I’m looking at except through the lens of my own—only sometimes reliable—feelings?

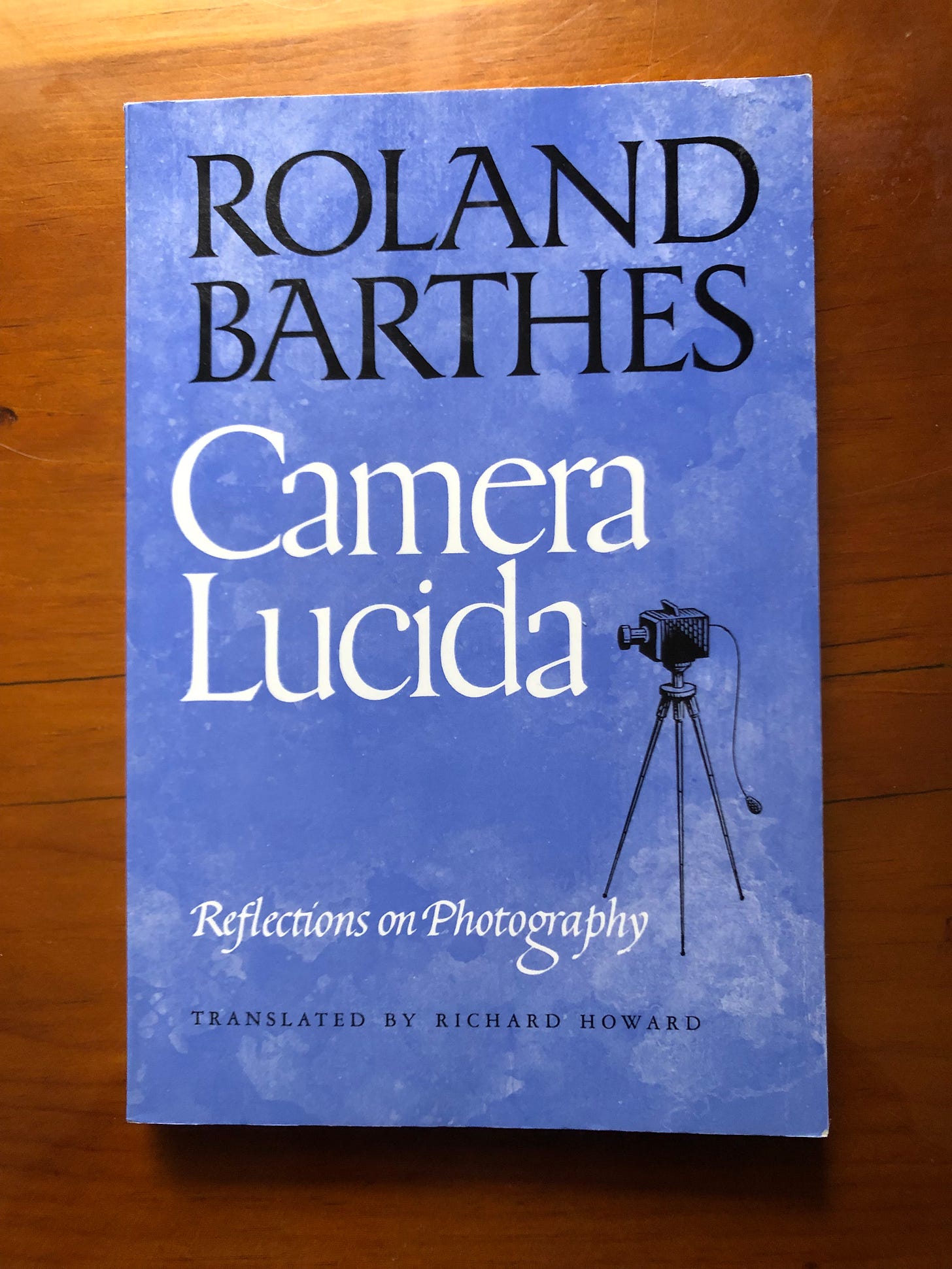

I’ve been trying to read Roland Barthes Camera Lucida, thinking that maybe I’ll learn something about how to consider and respond to photographs—and by extension other kinds of art. Barthes contends that the photo is good if something “pricks” him (I swear, only a man could have come up with that), but most of the examples he gives I find dull.

My friend Rebecca laughs when I tell her what I’m doing and says, “It’s all about his mother,” which ends up helping me understand Barthes and his photographic choices, but not so much what makes either a good photograph or an artwork I respond to.

But what I like or respond to may be very different from “good”—and do good and meaning go hand in hand? Good for me has always equated to something that moves me out of my comfort zone, challenges me, makes me see or think differently, which is as subjective as (or the same as?) Barthes’ “prick.” (Sorry.)

When I asked the photography teacher how to know if something was good, he asked if I liked it. Maybe I’m too Protestant, looking for standards outside myself, especially since I know harm can come from institutional standards. Groups get shut out, go unheard. But I need a place to start, a place that goes beyond my own limited understandings and emotions. If good art is bigger than I am, if it forces me to see the world in a new way (my own subjective definition, I know), then what tools is it using to do that? And what tools do I need to think about it? As a fledgling photographer, I need those tools to figure out whether what I’m looking at works.

The other problem for me with using only my own feelings or thoughts about an artwork is that my own knowledge and emotions are small—confined to one human and one set of experiences. That’s why I ask my students to respond first; I want them to start in their own experience, but from there to expand outward: consider intention, consider historical context, consider the elements of the form, consider unintended consequences. I want them to step outside themselves, which is where I want to go, too. If one doesn’t ask a viewer to respond beyond their own first subjective feeling or interpretation, my husband suggests, one is limiting art’s capacity to expand its viewers’ and thus society’s consciousness outward.

While Rothko may be speaking directly to me, I hope he’s speaking to more. I want that moment in front of the painting to connect me to you, for it to be communal, something that allows me to, as it were, reach through the painting and touch what it means to be human.

Thanks for reading. I always love hearing from you.

If you’re in Connecticut or Westchester, I’ll be hosting and reading with other writers in several different venues this month. I’d love to see you at an event:

Friday April 5, 7 PM: Byrd’s Books, Greenwood Avenue, Bethel, with Jack Powers, Van Hartmann, Rick Magee, and Amy Nawrocki

Wednesday, April 10, 5:30 – 7 PM: Sisters in Crime Panel on Mystery Writing: Stamford Library, Harry Bennet Branch, with J. A. Dayton, Wendy Whitman, Carole Shmurak, Gerri Lewis, and Amy Kierce

Thursday, April 18, 7 – 8 PM: Writers in Conversation (host): Norwalk Public Library, featuring David Rich and J. A. Dayton (thriller writers)

Saturday April 20, 11 AM: Stamford Library, Harry Bennet Branch, Van Hartmann and I will discuss about what it’s like to be married writers and share our work.

Sunday, May 5, 2 – 4 PM: Voices of Poetry, MOCA Westport, with poets Frederick Douglass-Knowles, Ralph Nazareth, Natasha Scripture; Music with Kristen Young and Joseph Bush

Follow me on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. My novels and poetry are available at Amazon and Bookshop.

Bear in mind, I am writing this on a crowded bus stuck in traffic returning from a day trip to Boston.

I am happy that you are continuing the discussion started in the former “Rothko” post. I love thinking about and considering art in general, and photography in particular.

First, I apologize if my wording was clumsy in the previous comment. My intention was not to say that art is a tabla rasa or blank slate, but that there is an interaction between the viewer and the artwork, at least in the best case- assuming the viewer finds enough interest or merit to expend the effort. I suppose it is not the worst thing if it is Rorschach-like and it helps the viewer to derive some personal meaning and interpretation.

I think it is also important to consider that art? And photography, exists in a context. It has a history and it has a body of critical examination.

The audience may or may not be aware of that context, and there is no requirement for them to be. But sometimes, that may also affect or color their experience with the artwork. And in creating the work, the artist may be responding to some aspect of historical or critical context. Not to mention socio-cultural or political (gasp).

I admit that I am undecided about this: I struggle with both the “elitism” of post modern art, but also with art that seems to pander to superficiality and commercialism. So where does that leave us? Is it possible for art to be both accessible and aesthetically pleasing, but not overly simplistic and dull?

For me Rothko found that balance, but how many people look at his paintings and say “huh?”?

In honor of Poetry Month and in honor of Rothko, I offer a poem:

Office Worker, 1967

Chuck each flap under the next,

Shuffle them like cards. Absolutely

Cover your heart. Crease

The boss’s dictums into perfect

Thirds before you shimmy them in.

Now splay the envelopes

Across the stained beige counter

So only the flaps show, and smear

A sponge across them all.

Turn the flaps down the way you turned

Yourself down, and smooth them shut.

Start home along the pale clay

Tinge of Chicago brick, ice water curbs,

Gray wind, the shoulders

Of people passing. Then, at the Art Institute,

Mark Rothko. Yellow

Proclamations holding the sun.

Light, a secret life you might step into.

Hope you never die.

Gail Howard